Dr Tavousi

Let me begin with a few introductory remarks before moving on to the more technical discussion.

When we examine this book—as Dr. Dehghani also noted—we must recognize that it is the product of a long-standing scholarly trajectory. It did not emerge in isolation. Many of its core themes trace back to the work of Verena Klemm, originally written in German and later translated into English by Etan Kohlberg.

Klemm’s article became a foundational reference for the “Imamate” entries in the Encyclopaedia Iranica—a publication that, alongside the Encyclopaedia of Islam, serves as one of the most authoritative sources in the field of Islamic Studies in the West.

In this regard, the book under discussion forms part of a broader, highly influential body of Islamicist scholarship produced in the Western academy. Following Klemm, Etan Kohlberg’s contributions—such as From Imamiyya to Ithnā ʿAshariyya, and his early documentation of the term Ithnā ʿAshariyya—are also of critical significance.

This leads us to a central question: In the face of this substantial intellectual tradition, what scholarly responses have we, as Shiʿi researchers and institutions, offered in return? What is our contribution to this ongoing discourse?

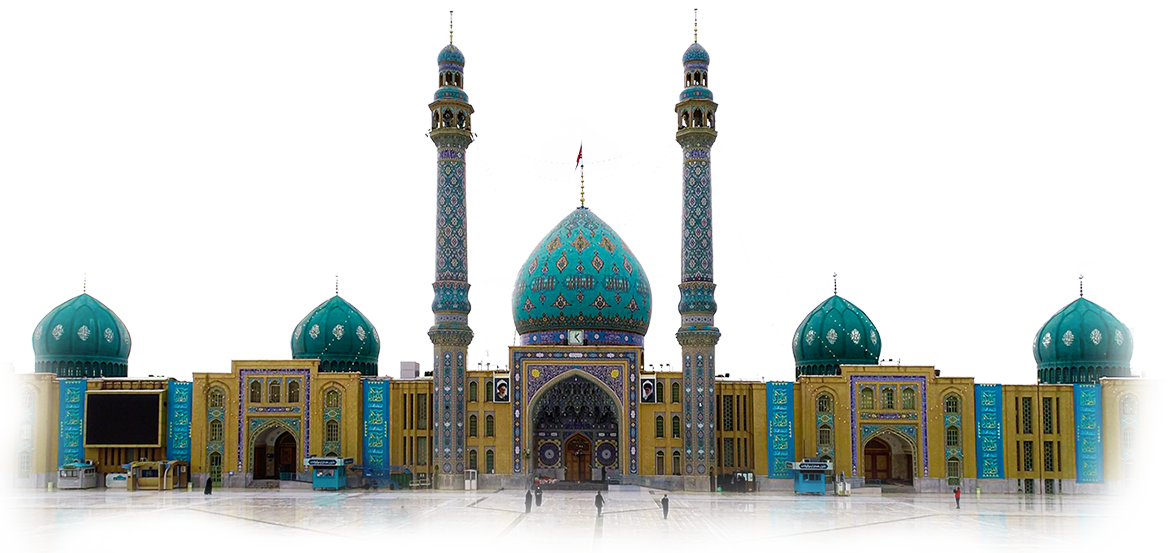

To this day, Klemm’s article has not even been translated into Persian—let alone subjected to a formal scholarly response. While there are numerous religious institutions in virtually every city, we have yet to deliver a serious and comprehensive response to critiques that challenge the very foundations of our theological framework. Meanwhile, Western scholars are engaging with—and indeed, deploying—our own sources: our ḥadīth, our historical reports, our classical texts, often using them as the basis for arguments that undermine our tradition.

On our part, we have made some humble efforts to respond adequately. One such effort was a critical article we published on the body of Mahdist literature produced in the first five centuries—a single piece in what we hope will be a broader and more systematic reply.[1] We aim to use internal textual cues and evidence from our own sources to mount a more robust and scholarly rebuttal.

We also published an article on Abū Sahl al-Nawbakhtī in the journal Shiʿah-Shināsī, in which we examined the claim—based on his alleged work—that the Twelfth Imam died and left behind a son, and that the line of Imams will continue in his progeny until the Day of Judgment.[2] This assertion, often cited by Western scholars, underpins a broader thesis: that the doctrine of twelve Imams, with the last being the awaited Mahdī, was a later development retroactively imposed onto earlier Shiʿi belief. This notion is not new; it stems from how Western scholars interpret our sources.

And what has been our response?

Unfortunately, some of our replies are deeply problematic. For example, Kohlberg argues that the number “twelve” is not explicitly mentioned in early works such as al-Maḥāsin by al-Barqī. In response, Dr. Alwīrī retorts, “It may not appear there, but it is found in Rijāl al-Barqī.” Yet this counterpoint is fundamentally flawed: as Ayatullāh Subḥānī has pointed out, Rijāl al-Barqī was not authored by al-Barqī himself, but by his grandson—some 50 to 60 years later. How can such a response be taken seriously as a scholarly rebuttal?[3]

This exchange highlights a broader issue: many of our responses suffer from methodological weaknesses. They are often flawed, insufficiently researched, or lack the analytical rigor required in academic discourse. If we continue to respond without precision, depth, and a critical self-assessment of our own methodologies, we risk unintentionally reinforcing the very critiques we aim to challenge.

Another persistent problem is the heavily sectarian and apologetic tone that characterizes much of our scholarly output. Rather than engaging with the academic frameworks and methodological tools employed by Western scholars, we often resort to polemics or confessional affirmations. For instance, during Eid al-Ghadīr, I explored how Western scholars approach the Ghadīr event. They have written extensively on the subject — and a notable example is Sayyid Muhammad Jafari’s English-language book, which retells the historical narrative using their scholarly idiom and within their methodological framework.[4] His work offers a model for how we might respond more effectively in academic terms.

Simply stating that a ḥadīth is “ṣaḥīḥ” (authentic) is no longer sufficient. In order to engage meaningfully in the academic arena, our responses must be grounded in rigorous methodology, intertextual analysis, and a careful awareness of how our sources are being interpreted by others.

Returning to the work of Edmund Hayes — Dr. Dehghani provided an excellent summary of his book. In fact, even someone unfamiliar with Agents of the Hidden Imam would gain a comprehensive understanding of its content through his presentation. That said, not all of Dr. Dehghani’s critiques were fully convincing.

He did, however, rightly highlight one of the most pressing methodological flaws common to many Western academic treatments of Islamic texts: selective citation and the application of double standards. This issue is not unique to Hayes but is part of a broader pattern within western scholarship.

To illustrate this, consider the example of Ignaz Goldziher. He cites a report in which the Prophet’s camel inadvertently steps on someone. The man then glares angrily at the Prophet, who becomes visibly upset. The man later tells a companion, “Had I remained any longer, a verse would have been revealed about me.” Goldziher uses this anecdote — reported by Ibn Saʿd, whose precision is questionable — to suggest that early Muslims believed the Qurʾān to be the Prophet’s own words, rather than divine revelation.

Yet in the same body of work, Goldziher encounters a report from Imam ʿAlī (ʿa) that demonstrates profound wisdom and political acumen. He immediately dismisses it as a later Shiʿi fabrication. Both narrations derive from the same source, yet one is accepted to support a broader thesis while the other is rejected because it conflicts with the scholar’s assumptions. Why accept one and reject the other?

This kind of cherry-picking and epistemological inconsistency is widespread. It reflects a deeper methodological problem — the privileging of certain narratives to fit preconceived frameworks while dismissing others that challenge those frameworks, often without sufficient justification.

Some of Dr. Dehghani’s critiques, however, warrant further scrutiny. For instance, his objection to Hayes’s use of “loaded” or “directional” language — such as “retrospective construction” or “manipulation” — is not entirely persuasive. Given that Hayes actually believes that elements of Twelver Shiʿism were constructed retrospectively by the Shiʿa community, it is only natural that he would use such terminology. One might ask: if a scholar genuinely views these developments as historical reconstructions, what alternative vocabulary could he reasonably be expected to use? In this context, the use of such terms is not necessarily an ideological imposition but a reflection of the author’s historiographical commitments.

Similarly, the criticism levelled against Hayes for citing al-Tanbīh fī al-Imama — attributed to Abū Sahl al-Nawbakhtī — appears unjustified. This text is, in fact, one of the most important early theological works in the Shiʿi tradition and survives, at least partially, in the writings of Shaykh al-Ṣadūq. Many contemporary scholars, have also relied on al-Tanbīh in academic work. In our previously mentioned article on Abū Sahl al-Nawbakhtī, we drew upon this very text to demonstrate that its author could not plausibly have held the view that the Twelfth Imam had passed away. Consider this: at the time of Abū Sahl’s own death, the Twelfth Imam would have been approximately 56 years old. Why would Abū Sahl — a highly regarded theologian — entertain the idea that someone of that age had already died, especially in the absence of compelling evidence?

What, then, does the book al-Tanbīh fī al-Imamah actually contain? It includes a range of core theological arguments that are foundational to Twelver Shiʿism, such as:

- The necessity of an explicitly designated (manṣūṣ) Imam

- The explicit designation (naṣṣ) of ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib (ʿa) as Imam

- The continuity of the Imamate through Imam al-Ḥasan al-ʿAskarī (ʿa), including the designation of the Twelfth Imam, both through scriptural and rational proofs

- Justifications for the concept of ghaybah (occultation)

- The necessity of believing in the Imam based on dalīl (evidence), rather than physical witnessing (mushāhada)

- The significance of the Four Deputies (al-Sufarāʾ), which implies that Abū Sahl accepted their legitimacy (despite having only witnessed three of them)

- The tawātur (mass transmission) of reports affirming the ghaybah

- The doctrine of two occultations — a lesser and a greater — with the second being more difficult

- A theological distinction between the concept of occultation as held by the Imamiyya and that of the Wāqifiyya

These are not marginal beliefs but constitute the very pillars of Twelver Shiʿī doctrine. Figures like Abū Sahl al-Nawbakhtī and Ibn Qiba dedicated themselves to formulating and preserving these doctrines in a period of theological turbulence. If Hayes is to critically engage with the intellectual formation of Twelver Shiʿism, what more appropriate source could he turn to than al-Tanbīh? To suggest that he should not reference it at all seems both unreasonable and dismissive of the weight the text carries within the Shiʿi theological tradition.

Similarly, al-Hidāyah al-Kubrā by al-Khaṣībī—despite ongoing scholarly debate over its structure and chapter ordering—remains a valid source for understanding early Shīʿī doctrines. The attribution of the book to al-Khaṣībī himself is generally accepted; the discussions revolve primarily around the internal arrangement and the possible later redaction of some parts. Even in the hypothetical case that one was to question its authorship, the text still serves as a valuable reflection of early Nusayrī (ʿAlawī) beliefs. We often cite this same work to support claims—such as the celebration of the birth of the Twelfth Imam in Karbalāʾ in the year 258 AH—to demonstrate the presence of this belief in early Shīʿī circles. But when other passages within the same text are perceived as problematic or incompatible with later theological formulations, we hastily dismiss the entire work. This kind of selective engagement is methodologically inconsistent.

As for Hayes’s use of cautious language—terms like “perhaps,” “it seems,” “it’s likely”—might be seen as a methodological flaw. While a few of my own teachers shared that view, I personally disagree. At most, one might argue that he overuses such language, but the mere use of these expressions is not inherently problematic. On the contrary, it reflects scholarly prudence and restraint—particularly when dealing with sources that were composed centuries after the events they describe. In fact, I have used similar expressions in my own doctoral dissertation and published works.

Moreover, such cautious phrasing is not unique to historical research. Even in the domain of jurisprudence (fiqh), scholars frequently use qualifiers such as “aḥwaṭ” (more cautious) or “aẓhar” (more apparent), and their legal opinions remain authoritative despite the presence of such language. So why should similar caution be viewed as a flaw in the field of historical inquiry?

In conclusion, I would like to once again express my gratitude to all those present. We are entering a critical phase in which even subtle historical shifts—such as moving the foundation of the institution of sifārah from Ḥusayn b. Rūḥ to Muḥammad b. ʿUthmān—can have far-reaching implications. These shifts are not merely chronological adjustments; they carry strategic weight. They offer us an opportunity to challenge broader narratives and to reassess longstanding assumptions in Western scholarship on Shiʿism. If approached rigorously, such interventions can serve as effective points of critique—turning the tools of historical inquiry into instruments of intellectual renewal.

Dr Kachaei

I sincerely wish Dr. Edmund Hayes could have joined us—at the very least via online attendance—so we could have engaged him directly on these issues.

[Interjection by the organizer: We did reach out to him, but he declined the invitation.]

Allow me to raise a critical terminological concern: I am personally quite averse to the use of the word nāʾib (deputy/representative). I consider it a kind of own goal that we’ve scored against ourselves by adopting this terminology. It provides easy ammunition for critics. A number of western scholars—including Verena Klemm, Edmund Hayes, Andrew Newman, and even polemical figures like Aḥmad al-Kātib—have used this very term as a basis to question our doctrines and historical claims.

We are constantly forced to respond by clarifying that this terminology does not originate in our early sources. In fact, prior to the 6th century AH, the term nāʾib was virtually non-existent in our textual tradition. The only known occurrence is in one of the writings of Shaykh al-Ṣadūq, and even there it does not carry the connotation that later scholars attributed to it. The prevalent and historically accurate term used in our early sources is wakīl (agent).

In my view, even the term ṣafīr (envoy) is problematic. It is not the terminology used by the Ahl al-Bayt (ʿa) themselves. We ought to remain faithful to the lexicon of our own tradition — to the very terms that appear in our earliest texts. Titles such as wakīl are firmly grounded in the sources and were actually used by the Imams and their companions.

Moreover, we have imposed upon these early agents a set of retroactive responsibilities and institutional roles that do not accurately reflect the historical realities of their time. With all due respect — and I say this without casting aspersions on their characters or their sincerity — these individuals were not the singular, centralized leaders of the entire Shiʿi community that we often portray them as today. The narrative that “the Imam had four deputies, and these four deputies managed and led the entire Shiʿi community” is a construction that came later.

Ironically, Hayes’s argument replicates this very error. While he questions the traditional number—proposing two or three figures instead of four—he nonetheless accepts the core premise: that a small, centralized leadership managed all of Imamī Shiʿism. This leads us to a fundamental problem: such assertions are not clearly substantiated in our earliest textual sources.

This brings me to a broader point: we must begin by critiquing ourselves. Mistakes have been made. Even if some of our most revered and learned scholars made these claims — and I affirm that they are towering figures in knowledge and piety — it does not render all of their assertions immune to scholarly critique. They are not maʿṣūmīn (infallible). And we must acknowledge the possibility that they, too, may have made interpretive errors.

In light of this, I would personally urge that we abandon the use of the term nāʾib altogether — at least in this theological and historical context. I say this not as a legal edict (fatwā), but as a principled personal stance grounded in study and research.

By adopting such terminology and framing, we are — perhaps unintentionally — side-lining the very role of the Imam himself. And that directly contradicts the foundational sources of our tradition. Our earliest and most authoritative texts never suggest such an interpretation. The references I am drawing from are not marginal; they are the core sources of Twelver Shiʿism.

So our critique must begin with ourselves. Many of these misconceptions are rooted in the way we ourselves have narrated and systematized our history. We have, in some ways, laid the groundwork for the very misunderstandings that later critics — including western scholars of Islam — have capitalized upon.

Let us be honest and self-critical: in these academic discussions, we are often engaging with Western scholars who have spent fifty, even seventy years immersed in the study of Shiʿism. They are highly trained in Arabic and Persian, and they possess deep familiarity with both the content and nuance of our sources.

So how can we, after only undergoing the type of rapid, surface-level training so common in our seminaries, presume to effectively critique such individuals? That kind of criticism lacks scholarly weight and will not be taken seriously — not by the broader academic community, and not even within our own learned circles. Speaking for myself, even I can easily detect when a response has been offered hastily or without proper methodological rigor.

Another important observation concerns the claim made by Dr. Edmund Hayes in the third chapter of his book — namely, that the Shiʿa faced a theological and organizational crisis at the beginning of the Minor Occultation. This is not merely his assertion; it is a conclusion supported by our own earliest sources.

For instance, in the work attributed to Abū Muḥammad al-Ḥasan ibn Mūsā al-Nawbakhtī, Firaq al-Shīʿa, the existence of deep division and doctrinal uncertainty following the martyrdom of Imam al-ʿAskarī (ʿa) is clearly described. Even if one were to question the attribution of this work to al-Nawbakhtī, we have an unquestionably authentic and contemporaneous source in al-Maqālāt wa-l-Firaq by Saʿd ibn ʿAbd Allāh al-Ashʿarī al-Qummī — a prominent 3rd/9th-century scholar and authority of the Qummī school. Writing during the very period of the Minor Occultation (circa 300–310 AH), Saʿd explicitly states, “We are in a state of confusion and crisis.”

This is not an isolated confession. Even Sunni sources from that period, such as al-Milal wa al-Niḥal by al-Shahrastānī and Maqālāt al-Islāmiyyīn by Abū al-Ḥasan al-Ashʿarī, acknowledge the internal fragmentation of the Shīʿī community after the passing of Imam al-ʿAskarī (ʿa). But more importantly, it is our own tradition — through both theological and historical documentation — that testifies to the reality of this moment of upheaval.

In this light, Hayes’s claim is not without merit. There was indeed a crisis. But what is often overlooked — and this is the central point — is the role of the Imam himself in resolving this crisis.

This is the argument I have consistently emphasized: that during these moments of existential threat, it is the Imam — and not any agent (wakīl) or future marjaʿ (juridical authority) — who prevents the collapse of the Shīʿī community. The Imam is not a passive symbol; he is the very axis of religious continuity. The very doctrine of Imamate is built on this foundational premise.

We see a parallel in the mission of the Prophet Muḥammad (ṣ): he descended upon a tribal society without an ummah. He built that ummah — but an ummah cannot produce a Prophet. Similarly, it is the Imam who reconstructs the broken community. He is the irreplaceable agent of renewal. If the Twelfth Imam had not survived — had he been martyred — could the community have simply fabricated an alternative institution of Imamate (ṣifārah)? Certainly not.

This is precisely why Imamate, like Prophethood, is not a secondary or derivative belief — it is a uṣūl (foundational tenet) of the faith. And the redemptive role of the Imam, as the preserver and restorer of the madhhab in times of fragmentation, is a dimension that demands greater theological and historical attention.

In one passage of his work, Edmund Hayes asserts that by the end of the Minor Occultation, the Shiʿa had come to believe that Imam al-ʿAskarī (ʿa) had left behind a son. On this specific point, I concur with his assessment. The behaviour and recorded actions of Imam al-ʿAskarī (ʿa) — as documented in our earliest sources — do indeed indicate that the birth of his son, the Twelfth Imam, was surrounded by a deliberate and strategic secrecy. This secrecy was not incidental, but essential to the protection of the Imam and the continuity of the Imamate.

It is inaccurate to imagine that Imam al-ʿAskarī (ʿa) made a public announcement proclaiming the birth of his son. To the contrary, our primary sources — both Shiʿi and non-Shiʿi — consistently point to the highly confidential nature of this event. The historical context must be carefully considered: by this time, the Abbasid regime was fully aware of prophetic and Imamī traditions that foretold the rise of a messianic figure, al-Thānī ʿAshar (the Twelfth), who would rise to dismantle oppressive rule and establish divine justice. This anticipation — and fear — on the part of the Abbasids led to heightened scrutiny and aggression toward Imam al-ʿAskarī (ʿa) and his household.

This is precisely why the birth of the Twelfth Imam (ʿa) was concealed. It was an act of preservation — not merely for the life of the child, but for the very survival of the wilāyah itself. The measures taken by Imam al-ʿAskarī (ʿa) were thus both theological and strategic.

It is telling, for example, that we have no surviving formal documentation or court record of Imam al-ʿAskarī’s marriage. What we do have is the famous and widely accepted narration from Lady Ḥakīma (ʿa) — herself a noble and trustworthy figure in the Ahl al-Bayt lineage. In this report, she testifies: “I was unaware of the birth of a son until the very night of his delivery.” This admission from such a close and devout relative underscores the depth of the secrecy surrounding the event.

Her testimony stands in stark contrast to that of Jaʿfar — whose unreliability and opposition to the Imam are well documented. Lady Ḥakīma’s account remains one of the most central and credible testimonies in the Imamī tradition regarding the birth of the Twelfth Imam and the circumstances of his early concealment.

In sum, the assertion that the belief in the existence of the son of Imam al-ʿAskarī (ʿa) emerged gradually is partially correct — but it must be contextualized by the unique socio-political pressures of the time. The doctrine was not invented retroactively; rather, it was carefully guarded from the outset due to existential threats posed by the ruling regime.

Imam al-ʿAskarī (ʿa) lived under intense Abbasid surveillance, where he had to protect his son, Imam al-Mahdī (ʿa), in secrecy. If anything had happened to that child, the line of Imamate would have ended. Unlike earlier Imams — such as Imam al-Ḥusayn (ʿa), who could name a clear successor — Imam al-ʿAskarī (ʿa) operated under extreme constraints. This is why narrations emphasize: “If not for the presence of the Ḥujjah, the earth would collapse.” The stakes were theological, not just historical.

Now, I have yet to delve into the core of the textual analysis. But at this point, it is important to foreground what Professor Edmund Hayes identifies as his central thesis — a point highlighted by our colleague Mr. Dehghani in his excellent summary. Hayes states quite clearly that his aim is to demonstrate how direct leadership by the Imams was gradually replaced by the invention of intermediary authority — a clerical bureaucracy not drawn from the Imams’ own family.

This, he says, is his theory.

And indeed, to propose a theory is the right of any scholar. That is the foundation of academic inquiry. However, a theory cannot be presented as self-evident while excluding competing interpretations. Nor can one build a thesis by selectively citing only those sources that conform to a predetermined conclusion, while marginalizing or omitting others that challenge it.

The methodology must be rigorous. Hayes relies on a particular corpus — and in many places, that corpus is limited. Alternative readings and broader textual engagement are often lacking. If the claim is that the institution of wakālah or sifārah was retroactively constructed, then all available textual evidence must be evaluated — not just those that conveniently support that claim.

In this regard, one of the major shortcomings of Hayes’s approach is precisely this: his reading privileges certain sources and voices while side-lining others. And in doing so, his otherwise interesting and sophisticated theory loses some of its scholarly balance.

Let me state this clearly: by God’s grace, I have never relied on Kitāb al-Hidāyah al-Kubrā or Dalāʾil al-Imamah as foundational sources in my work. I’ve consciously avoided using texts with questionable authenticity — not because everything in them is necessarily false, but because our method requires prioritizing the most reliable early sources.

In contrast, Edmund Hayes frequently cites such texts without the same caution. I don’t object to that in principle — but if you’re going to use those sources, then also engage with others, especially central collections like al-Kāfī. There are nearly fifty narrations in al-Kāfī describing the behaviour of Imam al-Mahdī (ʿa) during the Minor Occultation — many of them are historical, not just theological. It’s painful to say, but Hayes seems unfamiliar with these reports. And we, too, must admit that we haven’t done our part: these narrations deserve focused academic attention.

Hayes does not engage with many of the key reports from al-Kāfī — neither studying nor analysing them. Whether he overlooked them or chose to ignore them, the omission is real and weakens his narrative.

Moreover, despite claiming proficiency in Persian, Hayes rarely engages with contemporary Shiʿi scholarship. He reads Klemm, Modarressi, and Amir-Moezzi — but pays no attention to what Shiʿi scholars themselves are publishing today. That’s not mastery of Persian.

When we say someone is proficient in the language, we expect them to be reading our primary sources, following internal academic debates, and interacting with the latest Persian publications. I’ve heard that Etan Kohlberg now reads entire issues of Persian journals from Daftar Tablīghāt — that’s what deep scholarship looks like.

In comparison, Hayes still has a long way to go. He may one day become a respected scholarly authority on Shiʿism — even if his conclusions differ from ours — but that requires greater depth and engagement with the tradition. As it stands, that depth is missing.

One striking omission in Hayes’ work is his near-total neglect of ʿUthmān ibn Saʿīd — the first wakīl (agent) of the Hidden Imam. Rather than exploring his role, Hayes simply dismisses him— but without citing any clear source.

Yet, one of our earliest and most central sources, al-Kāfī by al-Kulaynī, offers a direct and detailed account. In volume one, around page 329, there’s a narration where Aḥmad ibn Isḥāq and ʿAbd Allāh ibn Jaʿfar al-Ḥimyarī meet ʿUthmān ibn Saʿīd and ask him about the Imam. He responds, “It is forbidden for you to ask his name,” and confirms that he has seen the Imam — even describing his appearance.

This is a key historical testimony. If Hayes rejects it, that’s his prerogative — but he should at least acknowledge and critically assess it. To not mention it at all, and then offer sweeping claims about this figure’s supposed corruption, is methodologically weak.

Even in Hayes’ discussion of the inheritance dispute between Imam al-ʿAskarī’s mother and Jaʿfar, ʿUthmān ibn Saʿīd is conspicuously absent — despite playing a documented role in such events.

This pattern of selective engagement is not just an academic disagreement — it’s a sign of deep bias in the material he chooses to cite and ignore.

[1] Saeed Tavousi Masror, Mahdieh Pakravan, and Zohreh Salarian, “Gunah-shināsī-i āthār-i Imāmīyah dar ḥawzah-i mahdawīyat tā qarn-i panjum-i hijrī-i qamarī (bar asās-i sanjah-hā-yi mawḍū‘, mashhab, va dawrah-i zamānī)” (“Typology of Imami Works in the Field of Mahdism until the Fifth Century AH [Based on the Criteria of Subject, Sect, and Time Period]”), Pazhūhishnāmah-i Kalām-i Taṭbīqī-i Shī‘ah (Shi‘a Comparative Theology Research Journal) 4, no. 7 (2023): 39-96, https://doi.org/10.22054/jcst.2024.76477.1138.

[2] Mahdieh Pakravan and Saeed Tavousi Masror, “Barrasī-i nisbat-i i‘tiqād bi wafāt-i Imām-i davāzdahum bi Abū Sahl Nūbakhthī” (“An Analysis of the Attribution of the Belief in the Death of the Twelfth Imam to Abū Sahl al-Nawbakhtī”), Faṣlnāmah-‘i ‘ilmī-i Shī‘ah Shināsī (Scientific Quarterly of Shi‘a Studies) 21, no. 84 (2023): 139-62, https://doi.org/10.22034/shistu.2025.2045376.2489.

[3] This issue has been dealt with extensively in Syed Ali Naqi Zaidi and Habib Mazahir. “From Ithnā-ʿAshariyya to Western Academia: Twelver Reactions to Historical Studies of the Formation of Twelver Doctrine.” Al-Qalam Journal, 2024.

[4] Jafri, S. Husain M. The Origins and Early Development of Shi’a Islam. London: Longman, 1979.